Compiling math statements to executables

We’re going to make our own compiler that is completely self sufficient. No libraries, no regex engine, no parser, no assembler. We will do everything by hand and we will end up with a working executable but what is the compiler? At its core, a compiler is a tool that translates from one language into another language. However, in more practical terms, we typically think of compilers as translating programming languages to executables.

Before we can translate we first check that the input adheres to the syntax rules, or grammar, of the programming language we are trying to compile. Depending on the language, the compiler may also perform semantic analysis. For example by checking type compatibility or ensuring that no null pointers are accessed. After confirming that the input code is syntactically and semantically correct, the compiler proceeds to the translation phase. A real compiler would split the translation into different steps, which makes optimizations easier. However in this post we will just translate mathematical expressions into the corresponding machine operations such that they can be inserted into an executable format so we skip that part.

Overview: What is the simplest compiler we can make?

Most resources on compiler construction start with simple math expressions—it’s like the “Hello World” of compiler building. We’ll begin by getting a high-level overview of what we need to do by considering the following expression:

4+6*22

The first step is to ensure that this is a valid math expression. However, to determine validity, we must first define what “valid” means. We do this by creating a grammar that describes all possible input strings that our compiler will accept. The grammar for our simple math language is defined as follows:

expr:

term + expr

term - expr

term

term:

num * term

num

num:

[0-9]+

Starting from the bottom, we define a number (num) as one or more digits. This definition does not allow for decimal numbers. In a real compiler, we would also limit the numbers based on the underlying data type. Here we will just assume that the user provides numbers that fit within an int32 data type…

However since we are only using a single type in our amazing “programming” language and we don’t even allow for variables we can skip the semantic checking that most compilers need to do.

Next, we see that both expr and term are defined recursively. A term might just be a number, so the string “31” would be a valid term. However, as indicated by the first line in the term definition, the string “31 * [term]” is recursively referring to another term. This other term might be just a number, or it could be another multiplication operation altogether. This recursive definition allows us to chain operations, effectively handling sequences of multiplication and addition of any length. Using the above grammar, we can parse our example into the following tree:

+

/ \

4 *

/ \

6 22

With this tree, the order of execution is fixed and can be easily determined by traversing the tree. All that remains is to look up the operation codes for addition and multiplication and write them into an executable.

Lexer

Before we can start implementing the grammar, we need to break the input down into smaller components called tokens. Our lexer will process the input character by character, determining whether each character should be associated with an existing token, create a new token, or be ignored.

Instead of converting the entire file into tokens at once, the lexer will be called by the parser as needed. It will always maintain the current position within the file and make this information available to the parser. As a result, if the parser encounters input that violates the grammar, it can provide precise feedback to the user by returning the exact line number and character offset where the error occurred. This will become clearer in the parser section, so please bear with me until then.

type Lexer struct {

line int

charOffset int

fileContent []byte

fileOffset int

}

For the actual tokenization I first defined a Token structure that contains two variables. The first variable holds the type of token. For example, if the current character in the input is a plus sign, it would be identified as a PLUS token. Many tokens, like the PLUS and MINUS tokens, do not have a value associated with them. However, when we encounter a number, we need to store that number so we can access it later during the actual translation process.

const (

NumToken = iota

PlusToken

MinusToken

MultiplicationToken

)

type Token struct {

name int

value int

}

To this end, I implemented two methods: advance() and currentToken(). The advance() method skips over any comments or whitespace, positioning our lexer at the start of the next token. The currentToken() method examines the characters at the current position and returns the appropriate token. This is straightforward for single-character tokens like PLUS or MINUS. However, for numbers, we need to read in multiple characters without actually advancing the lexer position. Since lexer is not entirely sure what token it is looking at yet we always want to keep the position of the lexer at the start of the current token until the entire token is accepted. So we look ahead of the lexer position until we encounter a non-digit character allowing us to capture the entire number as a single token.

Parser

The parser is responsible for checking that the input adheres to the grammar. Essentially, we translate the defined grammar into code to validate the input. We’ll demonstrate this using an example of an expression(term + expr|term - expr|term). According to the grammar, any expression starts with a term, so we will first check for that.

If we do not find a term, it indicates that the input is not a valid expression, and we should return an error.

func parseExpr(t *Tokenizer) error {

parse_err := parseTerm(t)

if parse_err != nil {

return parse_err

}

Next, we need to handle the recursive aspect of parsing, which involves adding any number of “+ term” or “- term” operations to the current expression. Instead of using recursive calls, I decided to use a for loop for this purpose.

The first step in the loop is to check the next token to see if it is a plus or minus sign. To achieve this, we request the current token from the lexer. If the current token is indeed a plus or minus sign, we proceed to handle the operation. If it is not, we conclude that the expression consists of just a single term and return nil, indicating no error. Notice that we are only examining the current token but not advancing the lexer. This allows us to return with no error and keep the current token unchanged. As such the same token could then be accepted by a different parsing step.

for {

token := t.currentToken()

operator := -1

switch token.name {

case PlusToken:

operator = PlusToken

case MinusToken:

operator = MinusToken

default:

return nil // expr is just a term

}

At this point, we have confirmed that we have encountered a plus or minus sign. Thus, we can safely advance the lexer to process the next token. Advancing the lexer may result in eof-error so we need to check for that.

err := t.advance()

if err != nil {

return &SyntaxError{

line: t.line,

offset: t.charOffset,

message: "File ended before Expr was completed.",

}

}

Since we know that the current token is either a plus or minus sign, we know that the next token must be a term. Therefore we can parse a term.

err = parseTerm(t)

global_bin = append(global_bin, translateOperation(operator)...)

In the overview we looked at a simple parse tree. Rather than creating a explicit tree structure we can see that we are already traversing the tree during the parsing process! To keep the example minimal we will handle parsing and translation simultaneously. We have called the parseTerm for the two operands of the current expression. Besides parsing a Term this function will also be responsible for translating the term which will eventually push its result onto the stack. This makes the two operands of the current expression available to us through the stack. We then add the machine codes that represent the current plus or minus operation to a global byte array. So in pseudocode our parseExpr() would translate “2 + 5” as:

// 2 + 5

parseTerm() -> push(2)

parseTerm() -> push(5)

translateOperation() ->

a = pop() // Retrieves 5

b = pop() // Retrieves 2

a = a + b // 2 + 5

push(a) // Push result (7)

Translation

The code we’ve just reviewed is already quite similar to what assembly instructions can achieve. So, our next step is simply to find the appropriate assembly instruction to carry out the action we’ve described. For instance, to push a 32-bit value onto the stack, we can use the opcode 0x68, followed by four bytes that represent our integer in little endian format.

func translateTerm(num int) []byte {

buf := new(bytes.Buffer)

buf.WriteByte(0x68) // push

binary.Write(buf, binary.LittleEndian, int32(num))

byts := buf.Bytes()

return byts

}

As we’ve seen in the parser, we simply add the bytes that translate the nodes of our parse tree to a global byte array in the correct order. To translate an operation, we do the same: we look up the appropriate operation codes to pop values from the stack into the respective registers, such as RAX and RBX. Then, we perform the operation on the values now stored in these registers and, finally, push the result back onto the stack.

func translateOperation(token int) []byte {

// pop args RAX, RBX

popped := []byte{0x58, 0x5B}

if token == PlusToken {

popped = append(popped,

[]byte{0x48, 0x01, 0xd8}...)

} else if token == MultiplicationToken {

...

// push %rax for next operation

popped = append(popped,[]byte{0x50}...)

return popped

}

This forms the heart of our executable. However, to ensure it runs on our system, we need to adhere to a specific executable format. Since I’m working on Linux, I’ve chosen the ELF format. In this format, we must specify to the operating system what type of executable it is dealing with and create a table of contents for the executable file. We need to indicate which parts of the file should be loaded into memory, where they should be loaded, and where the program should start. If you’re interested in more details about the executable format itself, feel free to check out the video I uploaded on the topic.

Once we’ve written a valid ELF file, we can start the program, but we won’t see any output since we’re only performing computations without printing anything to the user. Since our simple programming language only supports adding and multiplying numbers, I took a bit of a shortcut by adding a function to the bytecode that gets called after each statement to print the result. To print the resulting integer value, we need to convert it into its ASCII representation for each decimal position in the number. Creating such a function turned out to be a bit trickier than I expected, but it’s a fun little puzzle.

Assembly code to convert a number to acii

convert_and_print:

; Convert result to string

mov rbx, 10 ; Divisor for conversion loop

sub rsp, 32 ; Allocate 32 bytes on stack for string

mov rcx, rsp ; RCX points to the end of our buffer

convert_loop:

xor rdx, rdx ; Clear RDX before dividing RAX by 10

div rbx ; Divide RAX by 10, quotient in RAX, remainder in RDX

add dl, '0' ; Convert remainder to ASCII

dec rcx ; Move pointer

mov [rcx], dl ; Store character

test rax, rax ; Check if quotient is zero

jnz convert_loop ; If not zero, continue loop

print_result:

; Calculate string length

mov rdx, rsp

sub rdx, rcx ; RDX now contains the length of the string

; Print the entire string

mov rax, 1 ; syscall number for sys_write

mov rdi, 1 ; file descriptor 1 is stdout

mov rsi, rcx ; address of string start

syscall ; call kernel

add rsp, 32 ; Clean up the stack

ret

func call_print() []byte {

return []byte{

0xb9, 0x02, 0x10, 0x40, 0x00, 0xff, 0xd1,

}

}

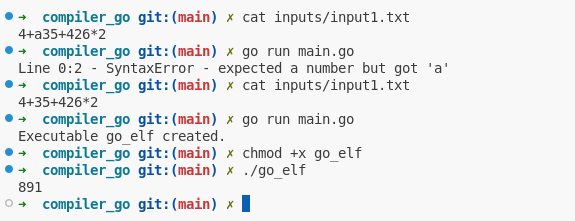

With that, we’ve created a fully functioning compiler. Given an input file with a mathematical expression, we can verify that the expression adheres to our grammar and provide useful feedback if it does not. If the expression is valid, the compiler proceeds to generate an executable file that embeds the expression, computes the result, and finally prints it out for us to see.

You can find the code for the entire project on GitHub